what is a karyotype and how can it be used to study human chromosomes

Chromosome Comparisons of Australian Scaptodrosophila Species

one

Pest and Environmental Accommodation Inquiry Group, School of Biosciences, Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Commonwealth of australia

2

Daintree Rainforest Observatory, James Melt University, Cape Tribulation, QLD 4873, Australia

3

Departamento de Genética due east Biologia Evolutiva, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão 277, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo 05508-090, SP, Brazil

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editor: Yehuda Ben-Shahar

Received: 21 February 2022 / Revised: 31 March 2022 / Accepted: 5 April 2022 / Published: 7 April 2022

Elementary Summary

Scaptodrosophila are a diverse group of flies that are widespread in Commonwealth of australia but take received express research attention. In this report, we characterized the chromosomes of 12 Scaptodrosophila species. We found that the structural changes in their chromosomes are very similar to those seen in Drosophila, a related genus of flies. This includes the amplification of repetitive elements and changes in chromosome length in small (dot) chromosomes and the sexual practice chromosomes. We also plant numerous weak points forth the arms of polytene chromosomes, which suggest the presence of internal repetitive sequences. Regions producing the nucleolus are at the same chromosome positions in Scaptodrosophila and Drosophila. These chromosomal studies provide a foundation for futurity genetic studies in Scaptodrosophila flies.

Abstract

The Scaptodrosophila represent a diverse group of Diptera closely related to Drosophila. Although they have radiated extensively in Australia, they have been the focus of few studies. Here, we characterized the karyotypes of 12 Scaptodrosophila species from several species groups and showed that they have undergone similar types of karyotypic change to those seen in Drosophila. This includes heterochromatin amplification involved in length changes of the sex and 'dot' chromosomes as well as the autosomes, specially in the coracina grouping of species. Numerous weak points forth the arms of the polytene chromosomes suggest the presence of internal repetitive sequence DNA, just these regions did not C-ring in mitotic chromosomes, and their analysis will depend on DNA sequencing. The nucleolar organizing regions (NORs) are at the same chromosome positions in Scaptodrosophila as in Drosophila, and the various mechanisms responsible for changing arm configurations besides announced to exist the same. These chromosomal studies provide a complementary resource to other investigations of this grouping, with several species currently being sequenced.

1. Introduction

The genus Scaptodrosophila is estimated to take diverged within the drosophilid lineage during the Cretaceous period nearly 70 million years agone. Further diversification occurred from the Eocene through the Holocene, about 50–0.vii 1000000 years ago [1]. The Scaptodrosophila were originally considered a subgenus of Drosophila and called Pholadoris in earlier studies [2,3], simply in a taxonomic revision of the family, Grimaldi [4] elevated the grouping to genus rank, which was supported by molecular information from DeSalle [v].

Of the 36 drosophilid genera represented in Australia, approximately a 3rd of the described species belong to the genus Scaptodrosophila. This prevalence of Scaptodrosophila in the Australasian drosophilid radiation is unique when compared to diversification elsewhere [six,seven]. Nevertheless, the genus has been the subject of relatively few scientific studies [viii,9]. The developmental requirements of most Scaptodrosophila species are unknown and appear to be restrictive since few species are widespread in urban environments [6]. Scaptodrosophila species accept been reported as feeding or breeding on tree sap, fungi, fruit and flowers [8,10]. Unlike Drosophila species, virtually cannot be collected on fruit baits, except for members of the coracina species grouping [xi]. Scaptodrosophila hibisci and S. aclinata breed in the flowers of native Hibiscus species [7,12]. There are too species that feed on and form galls in the stems of a bracken fern [13], while others feed on eucalyptus leaf litter in the crowns of tree ferns [8]. Species from the genus may accept important ecological functions such as in pollination and nutrient cycling, as well as in acting as a food source for other organisms.

Some coracina group species can exist reared on conventional Drosophila laboratory medium [nine]. However, other species must be supplied with fruit or flowers to stimulate egg laying. In the laboratory, mature larvae usually complete evolution by leaving their food vial and burrowing into surrounding sand or vermiculite to pupate [8]. Their 'skipping' or springing behavior facilitates this and likely aids their dispersal in nature. The practice of burrowing into ground material to pupate may have evolved as a machinery to protect the quiescent stage from environmental extremes and fires as well as predation and parasitism. Information technology is not surprising, therefore, that most species accept been difficult to maintain in the laboratory, particularly in long-term culture [8].

Given the difficulties in capturing and maintaining Scaptodrosophila species, few chromosomal studies have focused on Scaptodrosophila, with the most complete report carried out by Bock [11] on six members of the lativittata species circuitous of the coracina group. An early on study past Mather [three] presented a scheme of chromosome evolution. However, he considered them a subgenus of Drosophila, and his diagram of chromosome development mixed Drosophila and Scaptodrosophila (Pholadoris) species. A more contempo study by Wilson et al. [12] on South. hibisci indicated the presence of male recombination and neo-sexual activity chromosome germination in this species.

Here, we established conditions for the short-term culture of several Scaptodrosophila and used these lines to karyotype some species. Since Scaptodrosophila and Drosophila species have been separated for virtually 70 myr and adult morphology is all the same quite similar, we tested if the karyotypic changes that had occurred in species from these groups were besides similar. The cerebral ganglion chromosomes of the species that nosotros managed to culture were examined morphologically and also subjected to C-banding for constitutive heterochromatin localization and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), to locate ribosomal RNA genes. We attempted argent staining to examine the location of agile nucleolar organizing regions (NORs). We examined the polytene chromosomes only did not attempt a detailed banding comparison.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Species Examined

Species were mainly collected in northeastern Commonwealth of australia and identified by ane of us (M.S.) (Table 1). Several species are either new records for Australia or undescribed, and their classification is currently nether investigation.

Isofemale lines were established in the laboratory for the collected species. Although virtually of the Scaptodrosophila studied here have white larvae, larvae of Southward. novoguineensis and S. sp. aff. novoguineensis go purple equally they age. This purple paint occurs in both the fat body and hemolymph only appears to originate from the fat body. All feeding larvae had long posterior spiracles and showed the feature skipping behavior. The species that we studied preferred pupating in vermiculite that surrounded the culture vials. However, nosotros cultured two species, S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 and Southward. lativittata, for a period solely in food vials, and S. xanthorrhoeae can also be maintained indefinitely without admission to a vermiculite substrate.

Polytene chromosomes of S. nitidithorax were examined for inversion polymorphism. The mitotic karyotype of this species comes from Bock [xi]. Mitotic and polytene chromosomes of a pocket-size number of South. specensis had likewise previously been examined by Bock [11]. We C-banded several ganglion chromosome preparations of Due south. specensis. Polytene and mitotic chromosomes were examined for S. bryani and S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1. These techniques along with C-banding were completed for S. novoguineensis, Southward. lativittata and S. evanescens. All methodologies plus NOR localization were completed for S. xanthorrhoeae, S. claytoni, Due south. cancellata, Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata, Southward. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 and Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. novoguineensis.

The chromosome techniques used were the following: squash preparations of salivary gland polytene chromosomes in lacto-aceto orcein, squashes or drop spreads of brain mitoses stained with lacto-aceto orcein or Giemsa (Gibco, Adelaide, Australia), C-banded spreads of brain mitoses stained with Giemsa, NOR silver staining of mitotic spreads and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to identify the NORs (Tabular array ii).

2.two. Polytene Chromosome Squashes

Glands were removed in Drosophila Ringer's solution and fixed in fifty% acetic acid for seven–10 due south and 1N HCl for well-nigh 30 due south. They were then moved to a small driblet of mounting medium (sixty% acerb acid: lactic acid, 1:one) on a siliconized coverslip and allowed to clear before a very pocket-sized amount of lacto-acerb orcein stain was added and the coverslip picked upward with a cleaned slide and tapped/squashed to spread the chromosomes. To visualize the nucleolus, some preparations were fixed in 3:i ethanol:acetic acid or methanol:acetic acid.

ii.3. Cerebral Ganglion Chromosome Spreads

The cognitive ganglions were removed in Drosophila Ringer's solution, placed in 0.5% Na citrate for 10–15 min to spread the chromosomes and then fixed in several changes of methanol:acetic acid:water (eleven:eleven:1) for 1–ii min or longer. Tissue was then stained in lacto-acerb orcein on a siliconized coverslip for 10 min, a driblet of 60% acerb acrid was added and the training was picked up with a cleaned slide and squashed. For slides to exist used in C-banding, NOR silver staining or FISH, tissue was either squashed in lx% acerb acid and the coverslip removed after freezing in liquid nitrogen, or the cells were allowed to disassociate in 60% acetic acid and pocket-size volumes picked up with a micro-pipette, dropped on a make clean, warmed slide and air dried.

2.4. C-Banding

C-banding generally followed the technique used by Bedo [14] with a few variations. We used a 2–iii min incubation in 5% Ba(OH)2 at 50 °C followed by extensive washing in running tap h2o and deionized water. The Ba(OH)ii did not go completely into the solution, and all-encompassing washing in warm tap water was important for getting rid of some of the precipitate. This was followed past air drying, incubation for 1 h in 2X SSC (saline sodium citrate) buffer at 60 °C and a rinse in deionized water. The slide was so either stained immediately in four% Giemsa (Gibco) for 15–thirty min, or dried and stained the following day. This was followed past a quick rinse in deionized h2o. Afterward drying well, the preparation was mounted in Gurr'due south Neutral Mounting Media and examined.

two.5. NOR Silvery Staining

NOR silver staining was based on the technique of Howell and Black [15]. Since staining on mitotic chromosome figures was not consistent, various modifications of temperature and time [16,17,18], pH [xix], pre- and post-treatment of slides [xx,21,22,23,24] and historic period of the slide were tested. None were satisfactory in terms of giving consistent results. We tried heating in a microwave oven [25], but our preparations tended to be unevenly adult with no consistent deposition of silver grains over a particular chromosome.

2.6. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

Fluorescence in situ hybridization was carried out using two methods. The same result was achieved by both. 1. A Drosophila melanogaster Deoxyribonucleic acid clone, pDm238 in pBR322 [26], was labeled by nick translation and used as a probe every bit described previously [27]. This probe was an 11.v kb fragment that contained the 18S, 5.8S and 28S genes of D. melanogaster plus an intergenic spacer. 2. Total Drosophila RNA was used as a probe following the technique of Madalena et al. [28] or a slightly modified version of this technique. Approximately twoscore Drosophila melanogaster flies were etherized and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. They were homogenized in 0.viii mL Trizon (Invitrogen, Adelaide, Commonwealth of australia), and chloroform was added to a total volume of ane mL with mixing by Eppendorf inversion. After 15 min at iv °C, the training was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 10 °C for 10 min. One volume of frozen isopropanol was added to the extracted liquid phase with mixing, and the Eppendorf was kept in the freezer for 5 h. To recover the RNA, centrifugation was repeated as above and the pellet resuspended in formamide containing poly-(r)U (Sigma, Adelaide, Australia) (one µg/mL).

Chromosome spreads were treated with RNase A diluted in 2X SSC (0.ii mg/mL) for 3 h at room temperature. The slides were washed in 0.5X SSC, and chromosome DNA denaturation was performed by one of two techniques. In the first, slides were treated as in Madalena et al. [28]. A probe mixture (6 µL) of l% formamide, 2X SSPE (saline sodium phosphate EDTA buffer), 0.1% SDS and 100 ng of insect RNA mixed with poly (r)-U was applied to each air-stale slide and covered with a plastic coverslip. The slides were steam heated at 75 °C for denaturation and and so kept in a closed plastic box at 37 °C overnight or longer for hybridization. In the second technique, slides were incubated in 0.08 N NaOH for one min at room temperature and so washed in 0.5X SSC and kept in ice-cold ethanol until the hybridization procedure was carried out. The slides to be hybridized were stale, and the hybridization mixture, consisting of fifty% formamide containing RNA and 3X SSC, was applied under a plastic coverslip. The slides were incubated overnight at 37 °C.

Detection of the DNA-labeled probe was described in Stocker et al. [27]. The RNA probe was detected past incubation with caprine animal IgG anti-RNA.DNA hybrid [29] and detected with rabbit IgG anti-goat labeled with TRITC (Sigma), equally described in Madalena et al. [28] and Gorab et al. [30]. Slides were counterstained with iv′, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). They were mounted in Vectashield anti-fading solution (Vector Labs, Adelaide, Commonwealth of australia) and inspected with epifluorescence optics using Zeiss and Olympus microscopes equipped with CCD cameras and image analysis software.

3. Results

three.one. Lacto-Acetic Orcein Staining

The mitotic karyotypes of the 12 Scaptodrosophila species are shown in Tabular array 3. We have also included karyotypes of the other coracina species whose chromosomes were examined by Bock [eleven] as well as those of Due south. hibisci studied past Wilson et al. [12]. Well-nigh of the species examined are members of the coracina group. Two have tentatively been placed in the barkeri grouping, one is in the bryani grouping and the rest are not currently grouped with other species. Scaptodrosophila novoguineensis and South. sp. aff. novoguineensis are different species just very similar morphologically.

The karyotypes of ix species in the coracina group are very similar, peculiarly with respect to their autosomes. The tenth species, Southward. sp aff. cancellata, currently undescribed, lacks the metacentric autosome and instead has two acrocentrics (rods). The major divergence amidst these karyotypes is in the shape of the 'dot' and sexual activity chromosomes. 'Dot' chromosomes range from very small 'dots' (claytoni, evanescens, specensis) to large metacentrics (enigma). The X and Y chromosomes also take variable shapes from acrocentrics to submetacentrics.

Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 has a superficially like karyotype to the species in the coracina group, with a submetacentric Ten chromosome and a somewhat elongated 'dot' chromosome (Table three, Figure 1A insert). The Y mainly appears as an acrocentric. A 'dot' chromosome is clearly apparent in the polytene set and could often exist distinguished by its proximity to the nucleolus (Figure 1A). Polytene chromosomes in the S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 lines that were examined are as well polymorphic for a big terminal inversion on i of the autosomes (Effigy 1A,B). The other end of this autosome shows pairing betwixt repetitive sequences which is common in Scaptodrosophila (Figure 1B). Two boosted polymorphic inversions were observed in the original isofemale line of S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17.

The other species that we studied showed a variable number of arm fusions. Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 has two pairs of metacentric autosomes and ane pair of acrocentric autosomes. The 'dot' and X chromosomes take short artillery, and the Y often shows a central constriction (Effigy 2A). Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 and S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 have been tentatively placed in the barkeri group taxonomically, due to their superficial similarity to Due south. concolor, but this is probable to be revised upon examination of these species compared with blazon specimens of Due south. concolor, particularly in light of their chromosomal differences. The chromosomes of S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 more than closely resemble those of S. xanthorrhoeae (Figure 2B), which has not been assigned to a group. Withal, S. xanthorrhoeae has an acrocentric X and Y and pocket-size 'dots'. Scaptodrosophila novoguineensis and S. sp. aff. novoguineensis show farther reductions, having 2 metacentric autosome pairs, an acrocentric-shaped Ten and Y and pocket-sized 'dots'. Scaptodrosophila bryani has the most numerically reduced karyotype with ii metacentric chromosome pairs, an acrocentric 10 and Y and no 'dot'.

Scaptodrosophila hibisci [12] has a complex karyotype that appears very unlike from the Scaptodrosophila karyotypes that we have examined here. Information technology has a large metacentric chromosome pair with variable Giemsa staining of homologues, 3 pocket-size metacentric pairs, a small acrocentric and a small 'dot' chromosome pair. Experiments by Wilson et al. suggested neo-sex activity chromosome formation in this species [12]. While sex chromosomes take not been definitively identified, the authors advise that the big metacentrics could represent sex activity chromosomes, although additional translocations could have brought other chromosomes into the sex activity-determining organization [12].

The quality of the polytene spreads in the species nosotros examined varied, and good spreads proved difficult to obtain for most species. Scaptodrosophila chromosomes have numerous 'weak points' which are prone to breakage and the extrusion of small chromosome segments. This made information technology difficult to define individual chromosomes and distinguish the 'dot' chromosome from pocket-sized segments of other chromosomes that had become detached. An extreme example is shown in the squash of an S. bryani nucleus (Effigy 3A). Besides South. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17, possible dots could be observed in polytene sets of S. cancellata (Effigy 3B) and South. sp. aff. cancellata which both had metacentric dot chromosomes in mitotic spreads. 'Dot' chromosomes in polytene sets of other species were not repeatedly observed.

3.2. C-Banding

C-banding was carried out to examine the function of heterochromatin addition in karyotype changes amidst these Scaptodrosophila species. Some of the species examined by Bock [11] had large 'dot' chromosomes. Enlarged 'dot' chromosomes were also observed for several of the species in our investigation. We would await these chromosomes to exist C-band-positive. Nosotros were also interested in examining other chromosomes for the addition of C-banded heterochromatin regions. C-banding of ganglion prison cell chromosomes of the six coracina grouping species that were available gave the results shown in Figure iv. The three species with very small 'dot' chromosomes, S. claytoni, S. specensis and S. evanescens, accept a similar C-banding blueprint (Figure 4A). C-banded heterochromatin is consistently located at either side of the centromere of the metacentric autosomes and at the centromeric end of the acrocentric autosomes and the X chromosome. The Y chromosome is entirely C-ring-positive. Occasionally, internal C-bands were observed, such as those on the Ten chromosome of S. claytoni, simply these were non always present. Surprisingly, the 'dot' chromosomes of these three species are non ever C-ring-positive. Iii species accept larger, metacentric dot chromosomes. Except for its metacentric, C-ring-positive 'dot' chromosome, Due south. lativittata has a C-banding pattern similar to that described for the species above. Scaptodrosophila cancellata has more C-banding heterochromatin at the centromeric ends of its acrocentrics than the other species. Both S. cancellata and S. sp. aff. cancellata accept submetacentric X chromosomes with C-ring-positive short artillery and prominent C-band-positive metacentric 'dot' chromosomes (Figure 4B,C). Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 (Figure 4D) is non a member of the coracina group but, like them, has a pair of metacentric autosomes with C-banding well-nigh the centromere and C-bands near the centromeric end of the three acrocentric autosomes. However, the 'dot' chromosomes of this species take one part somewhat more darkly stained than the other, and the submetacentric Xs have only a fine C-band at the region of the presumed centromere (Figure 4D).

Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoeae and Southward. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 have similar karyotypes (Table 3), but Due south. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 was lost earlier C-banding had been carried out. The C-banded karyotype of S. xanthorrhoeae is shown in Effigy 4E. C-banded heterochromatin is observed at either side of the centromere of the metacentric chromosomes and at the centromeric ends of the acrocentrics. The 'dot' chromosome is C-band-positive in many, just non all, sets. Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 (Figure 3A) has a minor, metacentric 'dot' chromosome which often stains darkly in orcein squashes, similar to the long, evidently metacentric Y chromosome. This likely indicates that they would be C-band-positive.

Scaptodrosophila novoguineensis has the same karyotype as S. sp. aff. novoguineensis. C-banding is shown for S. sp. aff. novoguineensis, a new species which is currently being described (Figure 4F). C-band-positive heterochromatin is located at either side of the centromere of the two metacentric chromosomes and at the centromeric end of the X chromosome. The Y chromosome is totally C-ring-positive. The dot chromosome is positive in this preparation.

In these Scaptodrosophila species, no consistent internal C-bands in mitotic chromosomes were detected with the technique used, although the number of weak points and inverted repeats in polytene chromosomes suggested the presence of internal repetitive Deoxyribonucleic acid.

C-banding was conducted past Wilson et al. [12] for cognitive ganglion chromosomes of S. hibisci and is shown for 1 of the species' 2 chromosome i forms [12]. Considerable C-banded heterochromatin is located on all chromosomes, including entire arms of chromosomes two and 3 and almost an entire arm of chromosome 1. It is clear that heterochromatin additions and deletions have been important in shaping the karyotype of this species, perhaps changing acrocentrics to metacentrics, but further written report is required to decipher the changes that have occurred.

3.3. NOR Location

The location of the NOR was examined in S. cancellata, S. sp. aff. cancellata, Due south. claytoni, Due south. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17, S. xanthorrhoeae and S. sp. aff. novoguineensis. For all species except Due south. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17, in situ hybridization located the ribosomal Deoxyribonucleic acid genes on the sex chromosomes. In S. xanthorrhoeae (Effigy 5A,B), South. claytoni and S. sp aff. novoguineensis, one NOR was at the very end of the short heterochromatic block on the acrocentric X, probably just higher up the heterochromatin. Scaptodrosophila cancellata and S. sp. aff. cancellata had a submetacentric X, with the brusk arm almost completely heterochromatic (Figure 4B,C). In both species, the NOR was at the end of this arm (Figure 5C–F). In all of these species except South. claytoni, we found another NOR at ane cease of the Y chromosome (Figure 5B,D,F). For S. claytoni, we could not ascertain if the Y chromosome contained an rDNA site considering we never managed to find a male included among our in situ slides. For S. lativittata, which was not considered in the in situ hybridizations, the presence of distinctive satellites at the heterochromatic stop of the 10 chromosomes indicated that this was one of the NOR sites (A. Stocker, personal observations). In several species, there appeared to exist variation in the number of ribosomal cistrons between the two 10 chromosomes, just this needs further investigation.

Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 differed from the other species in having its ribosomal genes on the dot chromosome (Effigy 6A–C). In that location was very picayune heterochromatin present on the X chromosome of this species (Effigy 4D), and neither the X nor Y showed any rDNA.

Attempts to place the site of the active nucleolus in mitotic spreads using variations of the silver staining technique of Howell and Black [15] were mostly unsuccessful. The just consistent silvery staining was at the presumed nucleoli of interphase cells (Figure 7A1). Occasionally, a silver-stained nucleolus or fragment of a nucleolus could exist seen fastened to a prophase chromosome, simply it was usually unclear which chromosome was involved (Figure 7A1). When staining occurred on metaphase chromosomes, it was usually at centromeres. Rarely, staining occurred at a chromosome region that we knew from FISH results contained rDNA (Figure 7B). Most mitoses did not show silvery staining at all. Such variable results take also been observed in other species [22,31,32].

4. Word

4.1. C-Banding

C-banding identifies constitutive heterochromatin blocks which are more resistant than euchromatin to DNA removal [33]. The C-banding pattern of the Scaptodrosophila chromosomes was generally consequent (Figure eight), with the exception of the smaller 'dot' chromosomes which sometimes did non C-ring. The heterochromatic nature of the 'dot' chromosomes is a conserved feature throughout the drosophilids. Even so, their repeat level is considerably lower than pericentric heterochromatin since other cistron sequences are dispersed within them [34]. Since the genes in 'dot' chromosomes of different species are apparently the same, smaller 'dot' chromosomes should incorporate fewer repeats than larger 'dots' and therefore exist less heterochromatic. This could at least partially explain their lack, or variability, of C-banding in this study. In all the species nosotros studied, the Y chromosome C-banded very strongly. It was unremarkably impossible to discern clear structural variation along this chromosome, although sometimes there were constrictions or a region that looked darker than the rest. If the strength of C-banding is related to a loftier echo level, the Y chromosome Deoxyribonucleic acid must be very highly repetitious. There were no consequent C-bands within the arms of the mitotic chromosomes despite the presence of numerous weak points, indicating internal heterochromatin along the polytene arms.

The all-encompassing C-banded regions in South. hibisci [12] propose that the distinctive karyotype of this species may take been obtained by heterochromatin addition to acrocentrics, irresolute them to metacentrics or submetacentrics. The authors suggest that the rearranged banding between the chromosome ane homologues is probably caused past a pericentric inversion. Chromosome 1 is seen in iv forms and ii combinations. The forms with the stop satellite take characteristics of the X chromosome, with the satellite indicating the position of the NOR, which is commonly institute on the X in drosophilids. The sparse, intermediately banded chromosome that it is paired with in Type one cells is suggested by the authors to be a partially heterochromatized neo-Y chromosome. C-banding is not shown for this chromosome ane homologue, but if the pale Giemsa staining corresponds to the absenteeism of C-bands, the weak staining of this homologue may mean that other factors in addition to type and number of repeats are responsible for the presence of C-banding. Translocations between crucial Y regions and other chromosomes may also have played a role in the staining differences.

4.two. NOR Location

Well-nigh species in the genus Drosophila that accept been examined thus far have NORs on their sex chromosomes, and this is believed to exist the ancestral condition [35]. NOR-associated sequences probably help in pairing between the sex activity chromosomes during meiosis [36,37]. On the Drosophila X chromosomes, NORs were unremarkably located nearly the centromere at heterochromatic regions [35]. This was also the case in three of the Scaptodrosophila species for which the NOR position was examined (Effigy 8). In Drosophila hydei, however, the X is metacentric and the NOR is located near the distal stop of its heterochromatic arm [38]. This position is analogous with the results we obtained in Southward. cancellata and Due south. sp. aff. cancellata (Figure eight) and suggests that heterochromatin distension between the centromere and the NOR moved this region toward the stop of the arm during species evolution. The Y chromosome is entirely heterochromatic in Drosophila species, and NORs on this chromosome are more widely distributed [35]. In the grouping of Scaptodrosophila species examined, the NOR was always observed at one cease of the Y (Figure 8). Some species in the genus Drosophila take NORs on chromosomes other than the sexual activity chromosomes. Most of the members of the D. ananassae group take a NOR site on the 'dot' chromosome [35]. One of the Scaptodrosophila species that we examined, S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17, likewise has its NOR on the dot chromosome (Effigy 8). Two Hawaiian Drosophila species have a NOR on a dissimilar, non-heterochromatic autosome (the B element according to Mueller'due south [39] nomenclature), but the ring at which information technology is located is heterochromatic [40]. Despite the changes in the NOR position, it is consistently associated with heterochromatin regions.

4.3. Karyotype Development

In Drosophila, karyotype examination [39,41] and more than recent sequencing [42] have given convincing evidence that the primitive chromosome configuration is v pairs of acrocentrics (rods), including sex chromosomes, and one pair of 'dots', which are normally very modest and heterochromatic. When the chromosome number differed from this, cistron comparisons commonly could identify vi representative 'elements' chosen A–F, with A being the X chromosome and F the 'dot' chromosome. The Scaptodrosophila species in the current study have chromosome numbers ranging from 5 pairs of acrocentrics, a submetacentric X chromosome pair and a pair of 'dots', to ii metacentric pairs, acrocentric sex chromosomes and no 'dots'. Using arm changes and heterochromatin variation, we can suggest how some of these karyotypes originated from a hypothetical archaic one.

The most common karyotype amidst the species that we have examined is ane pair of metacentrics and three pairs of acrocentric autosomes, acrocentric or submetacentric sexual practice chromosomes and 'dot' chromosomes of varying sizes. This karyotype is found in all except ane member of the coracina grouping species and also in S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17. It can exist derived from the primitive karyotype by postulating a pericentric inversion in an acrocentric autosome that moved the centromere to a central position, pericentric inversions and heterochromatin amplification in some of the sexual practice chromosomes and heterochromatin amplification in 'dot' chromosomes (Figure 9). The infrequent karyotype among the coracina species is South. sp. aff. cancellata, which has five pairs of acrocentric autosomes, submetacentric sex chromosomes and big metacentric 'dot' chromosomes. This karyotype could have been obtained past dissociation of the metacentric autosome into two acrocentrics. Heterochromatin changes are very similar to those in Southward. cancellata. Since other members of the coracina grouping have an acrocentric 10 [xi], and in S. claytoni, the NOR is associated with centromeric heterochromatin, information technology is most probable that the heterochromatic arm of the Ten developed through extension of heterochromatin between the centromere and the NOR, leaving the NOR positioned near its end. Changes in the length of 'dot' chromosomes were common in the coracina species examined past Bock [xi] (Figure i, Effigy ii, Figure 3, Figure iv, Figure v and Effigy 6).

Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 was tentatively placed in the barkeri species group because of its superficial similarity to South. concolor, but its karyotype looked similar to that of the coracina species until the NOR sites were located. These were establish to exist on the 'dot' chromosomes rather than on the X and Y (Figure 10). The yellow/brown bodies and reddish/orange eyes of the developed flies were too quite different from the darker color of the coracina species that nosotros examined. The changes that formed the Southward. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 karyotype are hypothesized to accept been the same pericentric inversion described above, and transposition of the ribosomal DNA cistrons from the X to the dot chromosome as a pericentric inversion was formed in the 10 (Figure ten). In this procedure, the X appears to have lost well-nigh of its heterochromatin. It is possible that the rDNA on the dot chromosome came from the Y, since Y rDNA cistrons are also absent-minded. To resolve this question, we would need an intermediate situation with a NOR on the dot chromosome and another on one of the sexual activity chromosomes. With respect to its karyotype, this species appears to have diverged straight from the ancestor of the coracina group (Effigy 10).

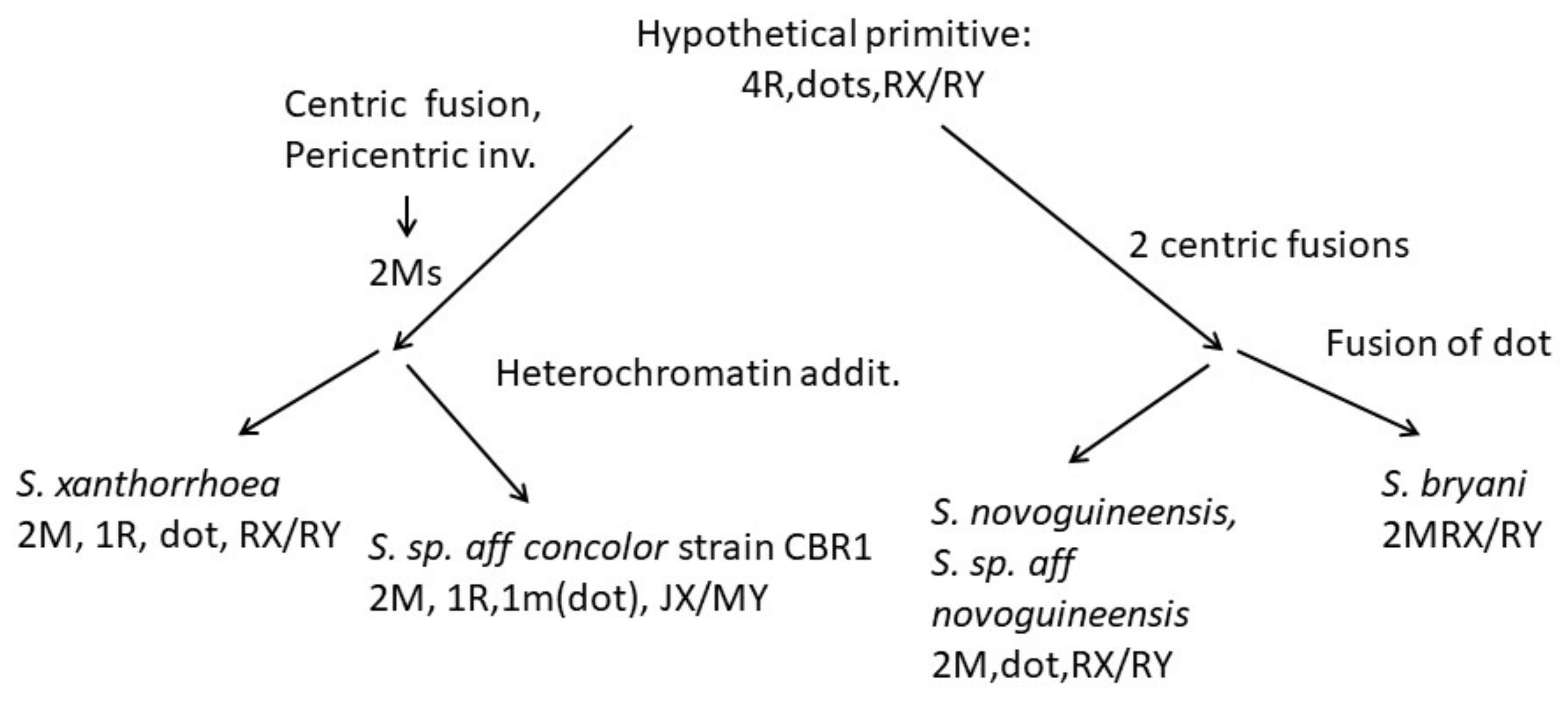

The other species bear witness a reduction in chromosome number and changes in chromosome shape, with elongation of chromosome brusk artillery in S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1, likewise tentatively placed in the barkeri species group (Effigy xi). Even so, S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 looks chromosomally like to Due south. xanthorrhoeae (Figure eleven), with a reduction in acrocentric autosomes to one and the gain of a smaller metacentric. A pericentric inversion could take formed the smaller metacentric, and a centromeric fusion between the two acrocentrics would class the larger acrocentric. Although we do not accept C-banding for South. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1, its curt arms, not nowadays in South. xanthorrhoeae, and larger metacentric 'dot' chromosomes are probably heterochromatic.

Further arm reduction is observed in S. novoguineensis and Due south. sp. aff. novoguineensis, both having karyotypes composed of ii pairs of metacentrics, a pair of dots and an acrocentric X chromosome. The about straightforward way that these changes could have evolved from a 5R, 1D karyotype is for two centric fusions to take occurred betwixt iv pairs of autosomes (Figure 11). Finally, S. bryani has lost the 'dot' chromosome, nigh likely by fusion with i of the longer chromosome arms. The absence of a 'dot' chromosome has been observed in several Drosophila species groups. In D. busckii [43], a basal Drosophila species, 'dot' chromosome genes are located near the heterochromatin of the X chromosome and also at a homologous region of the Y chromosome [44]. In situ hybridization also placed 'dot' chromosome genes of D. lebanonensis near the centromere of the acrocentric X chromosome (A element) [45]. Since X and 'dot' chromosomes have some like characteristics, it has been suggested that, in the aboriginal history of drosophilids, the 'dot' chromosome (F element) was part of the X chromosome [34]. In fact, sequencing and mapping of non-Drosophila Diptera have shown that the Mueller A chemical element is an autosome and the 'dot' chromosome is the female sex chromosome in these outgroup species [46]. Based on these results, we might hypothesize that 'dot' genes would be translocated near the centromere of the X chromosome in S. bryani. All the same, in six species of the willistoni species group, 'dot' chromosome genes were located near the centromere of the East element, also acrocentric [47]. Since the 10 and Y are the only acrocentrics in S. bryani, it seems likely that the F element would exist translocated to the X chromosome in this species. However, confirmation of this and other arm translocations will only come from time to come in situ hybridizations.

5. Conclusions

The Scaptodrosophila species we have examined indicate that, although this genus separated inside the drosophilid lineage relatively early on, the types of karyotypic change are like to those observed in Drosophila species and other features are too shared (Tabular array 4). Heterochromatin amplification appears to have been an important mechanism for structurally changing the arm length of the sexual activity and 'dot' chromosomes in both Scaptodrosophila and Drosophila. Such distension apparently adds artillery to other chromosomes as well [12]. In Drosophila species, heterochromatin amplification seems to have been concentrated in specific groups such as members of the ananassae species subgroup [35] and several Hawaiian groups [48] where the machinery and ground of this procedure take been discussed. In Scaptodrosophila, the amplification seems to exist particularly important in the coracina species grouping. Still, not enough species have been examined by mod banding techniques to be definitive about this. In the Drosophila karyotype list compiled by Clayton [49], a number of Scaptodrosophila karyotypes practice non show a 'dot' (F) chromosome. 1 reason for this could exist the presence in some species of a large 'dot' that was non recognized equally heterochromatic by the techniques used. Heterochromatin amplification could be a widespread machinery of karyotype evolution in the Scaptodrosophila. It is present in S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1, potentially a fellow member of the barkeri grouping, and in S. hibisci, one of the bloom-breeding species, where information technology could be related to neo-Y formation and male recombination. The locations of the NOR are the aforementioned in both Scaptodrosophila and Drosophila [35], as are the diverse mechanisms responsible for irresolute arm configurations. The many weak points and apparent inverted repeats observed in polytene chromosomes of Scaptodrosophila species may indicate a college number of transposable elements in this group, but proof of this would require more than investigation at the DNA level.

Of the estimated 230 described species of Scaptodrosophila [50], relatively few have been the subject of genetic studies. Preliminary whole genome DNA sequencing of some of these species (Rahul Rane, personal advice) has placed S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 as a relatively contempo divergence from the line leading to coracina species in the Scaptodrosophila tree. S. sp. aff. concolor CBR1 was non examined in these DNA comparisons, but the divergence between the chromosomes of the two species suggests that, although the flies may look superficially like to S. concolor, they may not exist closely related and could actually vest to unlike species groups. The line leading to S. xanthorrhoeae diverges earlier in the Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence comparisons, while S. bryani and Southward. novoguineensis form a separate and even earlier branching. Drosophila lebanonensis has been removed from the Scaptodrosophila lineage. The electric current analysis should provide a cytological framework for these ongoing genomic efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.South.; methodology, A.J.S. and Eastward.1000; investigation, A.J.S., One thousand.S. and Due east.G.; resource, E.G. and A.H.; writing—original draft training, A.J.Due south.; writing—review and editing, A.J.South., East.G., Thousand.S. and A.H.; visualization, A.J.S.; funding acquisition, A.H. All authors accept read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Commonwealth of australia's Science and Industry Endowment Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Argument

All information are bachelor inside the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mara Raimundo, Departamento de Genética due east Biologia Evolutiva, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil, for her assist with the fluorescence microscope.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Russo, C.A.K.; Mello, B.; Franzao, A.; Voloch, C.M. Phylogenetic assay and a time tree for a large drosophilid information set (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 169, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, West.B. The genus Drosophila (Diptera) in Eastern Queensland. two. Seasonal changes in a natural population 1952–1953. Aust. J. Zool. 1956, four, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, W.B. The genus Drosophila (Diptera) in Eastern Queensland. iii. Cytological evolution. Aust. J. Zool. 1956, iv, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, D.A. A phylogenetic revised classification of genera in the Drosophilidae (Diptera) 187. Bull. ANMH 1990, 197, 1–141. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalle, R. The phylogenetic relationships of flies in the family Drosophilidae deduced from mtDNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1992, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R.; Parsons, P.A. Adaptive radiation in the Subgenus Scaptodrosophila of Australian Drosophila. Nature 1975, 258, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvey, S.F.; Barker, J.S.F. Scaptodrosophila aclinata: A new hibiscus flower-breeding species related to S. hibisci (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Rec. Aust. Mus. 2001, 53, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R.; Parsons, P.A. The subgenus Scaptodrosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Syst. Entomol. 1978, 3, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R.; Parsons, P.A. Civilization methods for species of the Drosophila (Scaptodrosophila) coracina group. Dros. Inf. Serv. 1980, 55, 147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, I.R. Drosophilidae (Insecta: Diptera) in the Cooktown area of Northward Queensland. Aust. J. Zool. 1984, 32, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R. The chromosomes of half-dozen species of the Drosophila lativittata complex. Aust. J. Zool. 1984, 32, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.C.C.; Sunnucks, P.; Bedo, D.G.; Barker, J.F.S. Microsatellites reveal male recombination and neo-sex chromosome formation in Scaptodrosophila hibisci (Drosophilidae). Genet. Res. 2006, 87, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A.; Jackson, K.; Bock, I.R. Contrasting resource utilization in two Australian species of Drosophila Fallen (Diptera) feeding on the Bracken Fern Pteridium scopoli. Aust. J. Entomol. 1982, 21, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedo, D.G.C. Q and H banding in the analysis of Y chromosome rearrangements in Lucilia cuprina (Weidemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Chromosoma 1980, 77, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, W.1000.; Black, D.A. Controlled silverish staining of nucleolus organizer regions with a protective colloidal developer: A i-step method. Experientia 1980, 36, 11014–11015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirino, Thousand.One thousand.; Rossi, L.F.; Bressa, Grand.J.; Luaces, J.P.; Merani, Yard.S. Comparative study of mitotic chromosomes in 2 blowflies, Lucilia sericata and L. cluvia (Diptera, Calliphoridae), past C- and Thousand-similar banding patterns and rRNA loci, and implications for karyotype evolution. Comp. Cytogenet. 2015, 9, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploton, D.; Menager, M.; Jeannesson, P.; Himber, G.; Pigeon, F.; Adnet, J.J. Comeback in the staining and in the visualization of the argyophilic proteins of the nucleolar organizer region at the optical level. Histochem. J. 1986, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzbasioglu, D.; Unal, F. Karyotyping and NOR banding of Allium sativum L. (Liliaceae) cultivated in Turkey. Pak. J. Bot. 2004, 36, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lomholt, B.E.; Toft, J.M. The effect of pH on silver staining of nucleolus organizer regions. Stain. Technol. 1987, 62, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureate, J.R.; Ellison, J.R. Silverish staining for nucleolar organizer regions of vertebrate chromosomes. Stain. Technol. 1983, 58, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olert, J.; Sawatzki, G.; Kling, G.H.; Gebauer, J. Cytological and histochemical studies on the machinery of the selective silver staining of nucleolus organizer regions (NORs). Histochemistry 1979, 60, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, L.E. Improvements in the silver staining technique for nucleolar organizer regions (AgNOR). J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1993, 41, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilinski, S.K.; Bilinska, B. A new version of the Ag-NOR technique. A combination with DAPI staining. Histochem. J. 1996, 28, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, V.P.; Borges, A.R.; Fernandes, M.A. NOR sites detected by Ag-DAPI staining of an unusual autosome chromosome of Bradysia hygida (Diptera: Sciaridae) colocalize with C-banded heterochromatic region. Genetica 2002, 114, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavalcco, M.F.; Pazza, R. A rapid alternative technique for obtaining silver-positive patterns in chromosomes. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004, 27, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roiha, H.; Miller, R.J.; Forest, 50.C.; Glover, D.Chiliad. Arrangements and rearrangements of sequences flanking the ii types of rDNA insertion in D. melanogaster. Nature 1981, 290, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, A.J.; Gorab, E.; Amabis, J.M.; Lara, F.J.South. A molecular cytogenetic comparison between Rhynchosciara americana and Rhynchosciara hollaenderi (Diptera, Sciaridae). Genome 1993, 36, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madalena, C.R.K.; Amabis, J.M.; Stocker, A.J.; Gorab, E. The localization of ribosomal DNA in Sciaridae (Diptera: Nematocera) reassessed. Chromosome Res. 2007, 15, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Stollar, B.D. Comparing of poly (A)-poly(dT) and poly(I)-poly(dC) as immu- nogens for the induction of antibodies to RNA/DNA hybrids. Mol. Immunol. 1982, xix, 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Gorab, Eastward.; Amabis, J.1000.; Stocker, A.J.; Drummond, L.; Stollar, B.D. Potential sites of triple-helical nucleic acid germination in chromosomes of Rhynchosciara americana and Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosome Res. 2009, 17, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.D.; Dennis, E.S.; Honeycutt, R.I.; Contreras, N.; Peacock, W.J. Cytogenetics of the parthenogenetic grasshopper Warramaba virgo and its bisexual relatives. Chromosoma 1982, 85, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedo, D.Grand. Polytene and mitotic chromosome analysis in Ceratis capitana (Diptera; Tephritidae. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1986, 28, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmquist, Grand. The mechanism of C-banding: Depurination and β-elimination. Chromosoma 1979, 72, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddle, N.C.; Elgin, Southward.C.R. The Drosophila dot chromosome: Where genes flourish amidst repeats. Genetics 2018, 210, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Monti-Dedieu, L.; Chaminade, N.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S.; Aulard, South.; Lemeunier, F.; Montchamp-Moreau, C. Development of the chromosomal location of rDNA genes in ii Drosophila species subgroups: Ananassae and melanogaster. Heredity 2005, 94, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, B.D.; Karpen, G.H. Drosophila ribosomal RNA genes role equally an X-Y pairing site during male meiosis. Cell 1990, 61, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, B.D.; Habera, 50.; Vrana, J.A. Evidence that intergenic spacer repeats of Drosophila melanogaster rRNA genes function as 10-Y pairing sites in male meiosis, and a full general model for achiasmatic pairing. Genetics 1992, 132, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, W.; Link, B.; Leoncini, O. The location of the nucleolar organizer regions in Drosophila hydei. Chromosoma 1975, 51, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, H.J. Bearings of the 'Drosophila' work on systematics. In The New Systematics; Huxley, J., Ed.; Clarendon Printing: Oxford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 1940; pp. 185–268. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, W.D.; Bishop, J.1000.; Carson, H.L.; Frank, Thou.B. Location of the 18/28S ribosomal RNA genes in two Hawaiian Drosophila species by monoclonal immunological identification of RNA/Dna hybrids in situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. The states 1981, 78, 3751–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturtevant, A.H.; Novitski, E. The homologies of the chromosome elements in the genus Drosophila. Genetics 1941, 26, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, S.W.; Bhutkar, A.; McAllister, B.F.; Matsuda, M.; Matzkin, 50.M.; O'Grady, P.G.; Rohde, C.; Valente, Five.L.; Aguadé, Grand.; Anderson, W.Westward.; et al. Polytene chromosomal maps of 11 Drosophila species: The social club of genomic scaffolds inferred from genetic and concrete maps. Genetics 2008, 179, 1601–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivshenko, J.D. A cytogenetic study of the X chromosome of Drosophila busckii and its relation to phylogeny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.s.a. 1955, 41, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivshenko, J.D. New evidence for the homology of the brusk euchromatic elements oof the Ten and Y chromosomes of Drosophila busckii with the microchromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1959, 44, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaceit, M.; Juan, East. Fate of the dot chromosome genes in Drosophila willistoni and Scaptodrosophila lebanonensis adamant by in situ hybridization. Chromosome Res. 1998, half-dozen, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicoso, B.; Bachtrog, D. Reversal of an ancient sex chromosome to an autosome in Drosophila. Nature 2013, 499, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, Southward.; Yanina, P.; Lucia da Silva Valente, 5.; das Gracas Silva de Melo, Z.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, A.C.Fifty.; Montes, Grand.A.; Rohde, C. Cytogenetic mapping of the Muller F element genes in Drosophila willistoni grouping. Genetica 2014, 142, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, E.M.; Gall, G.J.; Jonas, M. Hawaiian Drosophila genomes: Size variation and evolutionary expansions. Genetica 2016, 144, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, F.E. Published karyotypes of the Drosophilidae. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 1998, 81, v–125. [Google Scholar]

- Van Klinken, R.D. Taxonomy and distribution of the coracina group of Scaptodrosophila (Duda: Drosophilidae) in Australia. Invertebr. Syst. 1997, 11, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Effigy 1. Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 salivary gland squash grooming. (A) Polytene nucleus. In = concluding inversion; arrow = 'dot' chromosome; * = nucleolar organizing region (NOR). Insert in upper left = mitotic set, X and Y = sex chromosomes. (B) Extended polytene chromosome. In = terminal inversion; pointer = inverted repeat. Bar = 10 µm.

Figure 1. Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 salivary gland squash preparation. (A) Polytene nucleus. In = concluding inversion; pointer = 'dot' chromosome; * = nucleolar organizing region (NOR). Insert in upper left = mitotic prepare, X and Y = sex activity chromosomes. (B) Extended polytene chromosome. In = terminal inversion; pointer = inverted echo. Bar = 10 µm.

Figure 2. Cognitive ganglia squashes (A) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1, orcein squash, 'dots', 10 and Y indicated. (B) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoeae, orcein squash, 'dot', X and Y indicated. Bar = 5 µm.

Effigy two. Cerebral ganglia squashes (A) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1, orcein squash, 'dots', X and Y indicated. (B) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoeae, orcein squash, 'dot', Ten and Y indicated. Bar = 5 µm.

Effigy 3. (A) Scaptodrosophila bryani polytene gear up. (B) Scaptodrosophila cancellata polytene set. Presumed 'dot' indicated. Bar = 10 µm.

Figure three. (A) Scaptodrosophila bryani polytene set. (B) Scaptodrosophila cancellata polytene set up. Presumed 'dot' indicated. Bar = 10 µm.

Figure four. C-banding of cognitive ganglia chromosomes. (A) Scaptodrosophila claytoni male. X shows two internal C-bands. Y and 'dots' are also indicated. (B) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata male, where X, Y and 'dots' are indicated. (C) Scaptodrosophila cancellata female, where X and 'dots' are indicated; Y is shown equally an insert. (D) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 male person, annotation the stake C-band on X. (E) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoea male person. (F) South. sp. aff. novoguineensis male person. Bar = 5 µm.

Effigy 4. C-banding of cerebral ganglia chromosomes. (A) Scaptodrosophila claytoni male person. Ten shows two internal C-bands. Y and 'dots' are likewise indicated. (B) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata male person, where Ten, Y and 'dots' are indicated. (C) Scaptodrosophila cancellata female, where X and 'dots' are indicated; Y is shown as an insert. (D) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 male, note the pale C-band on X. (E) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoea male. (F) Southward. sp. aff. novoguineensis male. Bar = 5 µm.

Figure 5. NOR sites shown by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Chromosomes stained with DAPI. (A) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoea female with NOR site on X chromosome (pointer). The rRNA technique was used. (B) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoea male with NOR sites on ends of Ten and Y chromosomes. Insert in upper left shows same photo with DAPI staining. Each chromosome or chromosome pair can exist distinguished by the shape of its heterochromatin. Y (arrow) is completely heterochromatic. 10 has a single round heterochromatic end (arrow). An rDNA probe was used. (C) Scaptodrosophila cancellata female person with NOR site at end of Ten chromosome heterochromatic arm (arrow). The rRNA technique was used. (D) Scaptodrosophila cancellata male fix. Heterochromatic Y has NOR site at one end (arrow). X has pale NOR site at end of heterochromatic arm (arrow). An rDNA probe was used. (East) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata female with site at cease of heterochromatic arm of X (arrows). An rDNA probe was used. (F) Scaptodrosophila sp. cancellata male person with stiff site on heterochromatic Y chromosome (pointer) and weaker site at heterochromatic end of Ten (arrow). An rDNA probe was used.

Effigy 5. NOR sites shown by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Chromosomes stained with DAPI. (A) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoea female with NOR site on Ten chromosome (arrow). The rRNA technique was used. (B) Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoea male with NOR sites on ends of X and Y chromosomes. Insert in upper left shows same photo with DAPI staining. Each chromosome or chromosome pair can be distinguished by the shape of its heterochromatin. Y (arrow) is completely heterochromatic. 10 has a unmarried round heterochromatic cease (arrow). An rDNA probe was used. (C) Scaptodrosophila cancellata female with NOR site at end of Ten chromosome heterochromatic arm (arrow). The rRNA technique was used. (D) Scaptodrosophila cancellata male person fix. Heterochromatic Y has NOR site at one cease (arrow). Ten has pale NOR site at end of heterochromatic arm (arrow). An rDNA probe was used. (E) Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata female with site at stop of heterochromatic arm of X (arrows). An rDNA probe was used. (F) Scaptodrosophila sp. cancellata male with stiff site on heterochromatic Y chromosome (arrow) and weaker site at heterochromatic finish of X (pointer). An rDNA probe was used.

Figure vi. NOR sites on Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 chromosomes every bit shown past FISH. (A) Female with hybridization to 'dot' chromosomes (arrow). The rRNA technique was used. (B) Male with hybridization to 'dot' chromosomes. Second arrow indicates heterochromatic Y chromosome. An rDNA probe was used. (C) Polytene chromosomes with hybridization to nucleolar RNA. The rRNA technique was used. Insert shows close association between polytene 'dot' chromosome and nucleolus with extending strands of DNA.

Figure six. NOR sites on Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 chromosomes as shown by FISH. (A) Female with hybridization to 'dot' chromosomes (arrow). The rRNA technique was used. (B) Male with hybridization to 'dot' chromosomes. Second arrow indicates heterochromatic Y chromosome. An rDNA probe was used. (C) Polytene chromosomes with hybridization to nucleolar RNA. The rRNA technique was used. Insert shows shut association between polytene 'dot' chromosome and nucleolus with extending strands of DNA.

Figure 7. Argent staining technique showing Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata chromosomes. (A) Interphase and early mitotic cells with nucleolar staining. (A1) Bright field. (A2) Stage with distinctive coloration of nucleolus. Chromosomal origin of nucleolar fragment unknown. (B) Mitotic prison cell with silver-positive spot over apparent X chromosome. Bar = 5 µm. Insert shows phase contrast of the same cell.

Figure 7. Silvery staining technique showing Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata chromosomes. (A) Interphase and early on mitotic cells with nucleolar staining. (A1) Bright field. (A2) Phase with distinctive coloration of nucleolus. Chromosomal origin of nucleolar fragment unknown. (B) Mitotic jail cell with silver-positive spot over apparent X chromosome. Bar = 5 µm. Insert shows phase contrast of the same cell.

Effigy 8. Ideograms of chromosomes examined. C = C-banded heterochromatic region; N = NOR location past FISH; ?North = possible NOR (FISH not conducted for male); Nsat = NOR identified by satellite location; North* = FISH conducted for S. sp aff. novoguineensis.

Figure viii. Ideograms of chromosomes examined. C = C-banded heterochromatic region; N = NOR location past FISH; ?N = possible NOR (FISH not conducted for male); Nsat = NOR identified by satellite location; N* = FISH conducted for S. sp aff. novoguineensis.

Figure 9. A scheme showing possible chromosome changes from an ancestral five acrocentric plus dot karyotype that could have given rise to members of the coracina group of species.

Figure 9. A scheme showing possible chromosome changes from an bequeathed five acrocentric plus dot karyotype that could have given rise to members of the coracina group of species.

Figure ten. Scheme of changes in an ancestral karyotype that could take resulted in the formation of the S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 karyotype.

Effigy 10. Scheme of changes in an ancestral karyotype that could have resulted in the formation of the S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 karyotype.

Figure xi. Possible karyotypic changes giving rise to other Scaptodrosophila species studied.

Figure 11. Possible karyotypic changes giving ascent to other Scaptodrosophila species studied.

Table one. List of species and collection site of species examined in this report.

Table 1. List of species and drove site of species examined in this study.

| Species | Species Group | Collection Site |

|---|---|---|

| Scaptodrosophila cancellata | coracina | Lake Placid, Qld (September 2011) |

| Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata | coracina | Lake Placid, Qld (April 2012) |

| Scaptodrosophila claytoni | coracina | Nowra, NSW (March 2014) |

| Scaptodrosophila evanescens | coracina | Nowra, NSW (March 2014) |

| Scaptodrosophila specensis | coracina | Lake Placid, Qld (April 2012) |

| Scaptodrosophila lativittata * | coracina | Melbourne, Vic (March 2021) |

| Scaptodrosophila nitidithorax | coracina | South Perth, WA (February 2021) |

| Southward. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 | barkeri? | Townsville, Qld (September 2011) |

| Due south. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 | barkeri? | Lake Placid, Qld (September 2011) |

| Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoeae | Lake Placid, Qld (September 2011) | |

| Scaptodrosophila novoguineensis | Mossman, Qld (May 2011) | |

| Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. novoguineensis | Lake Placid, Qld (April 2013) | |

| Scaptodrosophila bryani | bryani | Lake Placid, Qld (May 2011) |

Tabular array 2. Methods used.

| Species | Chromosomes Examined | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Scaptodrosophila cancellata | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| Due south. sp aff cancellata | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. claytoni | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, rDNA FISH (female) |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. evanescens | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. specensis | ganglion | C-banding |

| polytene | not done | |

| S. lativittata | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, NOR from satellites |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. nitidithorax * | polytene | squash preparation |

| S. sp. aff concolor strain CBN17 | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. sp. aff concolor strain CBR1 | ganglion | orcein staining |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. xanthorrhoeae | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| South. novoguineensis | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. sp. aff novoguineensis | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. bryani | ganglion | orcein staining |

| polytene | squash preparation |

Table 3. Karyotypes of the species (G = large metacentric; m = pocket-sized metacentric; J = submetacentric; R = rod or acrocentric; D = dot) * from Bock [11], and # from Wilson et al. [12].

Tabular array 3. Karyotypes of the species (M = large metacentric; m = small-scale metacentric; J = submetacentric; R = rod or acrocentric; D = dot) * from Bock [11], and # from Wilson et al. [12].

| Species | Female Brain | Male Brain | Total Chromosomes, Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cancellata | 1M3R1mDJX | 1M3R1mDJXRY | half-dozen pairs = 9 arms |

| Southward. sp. aff. cancellata | 5R1mDJX | 5R1mDJXmY | 7 pairs = nine arms |

| S. claytoni | 1M3R1DRX | 1M3R1DRXRY | 6 pairs = 7arms |

| S. evanescens | 1M3R1DRX | 1M3R1DRXRY | 6 pairs = 7arms |

| Due south. specensis | 1M3R1DRX | 1M3R1DRXRY | six pairs = 7arms |

| South. lativittata | 1M3R1mDRX | 1M3R1mDRXRY | half dozen pairs = 8 arms |

| S. nitidithorax * | 1M3R1JDRX | 1M3R1JDRXRY | half dozen pairs = eight arms |

| S. enigma * | 1M3R1MDJX | 1M3R1MDJXJY | half-dozen pairs = 9 artillery |

| South. howensis * | 1M3R1MDJX | 1M3R1MDJXJY | half dozen pairs = 9 arms |

| S. novamaculosa * | 1M3R1JDJX | 1M3R1JDJXRY | 6 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 | 1M3R1DJX | 1M3R1DJXRY | half-dozen pairs = eight arms |

| S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 | 2M1R1mDJX | 2M1R1mDJXMY | 5 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. xanthorrhoeae | 2M1R1DRX | 2M1R1DRXRY | 5 pairs = 7 artillery |

| S. novoguineensis | 2M1DRX | 2M1DRXRY | four pairs = 6 arms |

| S. sp. aff. novoguineensis | 2M1DRX | 2M1DRXRY | iv pairs = six arms |

| Southward. bryani | 2MRX | 2MRXRY | 3 pairs = 5 arms |

| S. hibisci # | 1M3m1J1D $ | 1M3m1J1D $ | 6 pairs = ten arms |

Table four. Comparing of Scaptodrosophila with Drosophila.

Table four. Comparing of Scaptodrosophila with Drosophila.

| Characteristic | Observations in Drosophila | Observations in Scaptodrosophila |

|---|---|---|

| Link to ancestral karyotype | Aye | Not observed |

| Heterochromatin location | Centromeres, 'dots', Y, some arms | Equally for Drosophila |

| NORs | 10, Y ordinarily, dot, occasionally others | X, Y, dot |

| Dots | Size varies, heterochromatic merely C-banding variable, usually present in polytene set | Size varies, heterochromatic just C-banding variable, normally absent-minded in polytene prepare |

| Mitotic chromosomes | A–F arms, syntenic | A–F arms, assumed |

| Polytene chromosomes | Generally spread well | Spread poorly, weak points, repeats |

| Publisher'south Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This commodity is an open admission article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Eatables Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/13/4/364/htm

Publicar un comentario for "what is a karyotype and how can it be used to study human chromosomes"